Last month I left you all with the homework of mapping you and your horses physical asymmetry. That likely produced a whole bunch of information, but now the question is, what to do about it? This month, we will focus on making some delicious lemonade from all those lemons you gathered. Remember that information is good, as it will help you become a more aware (and consequently more symmetrical and straight) rider. Lets discuss some activities and exercises that will address all the crookedness we have in our bodies and our horses bodies.

First, on the subject of ourselves, there are some excellent books out there that address yoga and pilates for equestrians. These can be very beneficial in finding some appropriate exercises for your bodies crookedness. I have had great luck in fixing my own asymmetry through the use of chiropractics and massage. As anyone who has ridden in my saddle can attest to, one of my legs is longer than the other, so one of my stirrups was always adjusted 1 hole lower. Recently, by getting some good massages, and some excellent chiropractic work, that is no longer the case. My sciatic nerve pain that accompanied this is also gone – which has been a godsend. Just being aware of your crookedness should help fix some of it.

Pay attention to your bodies symmetry when in the saddle especially. Sylvia Loch, author of “Dressage in Lightness,” suggests that you align the zipper on your jacket and breeches with your horses wither. I find that to be a helpful visual. The softer you are through your body, the less tension you hold in your joints, the more symmetrical and straight you will be. When you mount up, spend a minute stretching and aligning your body. Lift your legs off of the saddle and make sure they hang softly from your psoas muscle, through your hip joint, your knee and your ankle. Educate yourself about the importance of the psoas muscle and it’s connection to physical tension and stress. Perhaps that is a subject for another article another day… As you soften through your body, you might even have to let out your stirrups a hole, and you should begin to feel taller. Check your shoulders, neck, elbows, wrists and fingers for excessive tension. Soft heavy joints are crucial to a relaxed, straight, effective rider. If you are tense you will kill the lightness and impulsion in your horse, and will not be able to feel them. We will go into this in more detail next month.

For now, we will focus for the rest of the article on the horse. In the horses body, asymmetry is caused by two related reasons. First, there is structural asymmetry that should first be addressed by good bodywork. I find the skill and feel of the practitioner is more important than the specific modality used. I have had success correcting crookedness employing chiropractic work, acupuncture, massage, essential oils, dental work, farrier work, and the Masterson Method among others. Find what combo works for your horse, and then check in on their body regularly with it. That should always be the first step in working towards straightness.

After we address the underlying structural asymmetry, or at least begin to, then we must address and retrain the muscle memory of the horse. That is where the exercises I will be suggesting come in to play. They all have one thing in common. They focus on strengthening the inside hind leg. Why is this so important you might ask? Well, when a horse walks straight along a wall, their outside shoulder will naturally align with the wall. A horse is wider behind than in front though, so by aligning their shoulder with the wall, their hips will track to the inside. This will encourage their inside hind leg to play a very passive role in supporting the weight and balance of the horse. Biomechanically speaking, it is way better for the horses body if the hind legs step under the horse more, towards the center line, and under the weight of the haunches. Now I’m not suggesting any sort of weird contortion on the horses part, as that would obviously put undue stress on their joints. What I am saying though is, that most horses do not step under that balance point naturally, especially if not trained to do it early on. This results in a weak hind end, and a horse that drags itself along, and is heavy on the front end. And don’t think that if you are a trail rider you are off the hook – because it happens on the trail as well. The “wall” on the trail is just the edge of the trail… Naturally, because we are talking about crookedness here, most horses will have an especially hard time stepping under with either their left or right hind leg. Jim Masterson says that most horses are “right front, left hind horses,” which means that it is harder for them to step under their body with their right hind.

So how do we fix this? First, learn what shoulder fore is, and then ride in shoulder fore whenever you are trying to ride straight in a specific direction. And no, this does not apply only to stuffy dressage riders. Everyone should know what shoulder fore is, and every young horse should be taught shoulder fore early on in their education. Simply put, all you are doing in shoulder fore is moving your horses shoulders slightly to the inside. This simple adjustment will align the horses shoulders with their haunches. Google some images of shoulder fore if this is confusing to you. It is important to bring the shoulder in off the wall, rather than push the hindquarters to the outside for the shoulder fore to be effective. Using the outside rein almost as if you were neck reining will help with this. In this simple and perhaps boring exercise, we will be laying the foundation for symmetry, strength and lightness in our riding.

After mastering the shoulder fore, learn about and practice the “shoulder in” – which is essentially auntie or uncle shoulder fore. In shoulder in, the horse essentially is at an angle of 30 degrees to the wall, bent around the riders inside leg, and looking away from the direction of travel. This should place the horses steps on “three tracks,” meaning that the outside hind will make one track, the inside hind will follow in the track of the outside front leg, and the inside front leg will make the third track. “Four tracks” would result in more of an angle off the wall, and is also acceptable. Again, visuals are super helpful, so fire up the mighty Google, and search away.

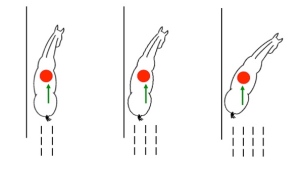

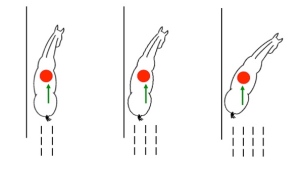

Left to right:

Shoulder fore,

Shoulder in on 3 tracks,

Shoulder in on 4 tracks.

Second, we fix our horses muscle memory of crookedness by incorporating LOTS of circles, serpentines, and changes of rein into our riding. If you think about it, when circling, it will be much easier for the horses inside hind to reach under their body and support the weight of their hind end. With that in mind, I find the following exercises to be very helpful in developing straightness.

Ride every corner, whether it is on a trail, in a field, or in an arena as a right angle. There are two ways to ride a corner: First, ask your horse to step to the inside with their outside front leg. This should not result in them dropping their inside shoulder, rather it should feel like their outside shoulder is pushing to the inside. This is a feeling that will be familiar to those who neck rein, and will feel less familiar to those who direct rein. This movement emphasizes the importance of the outside rein. On the next corner, ask your horses inside hind leg to step under and towards the outside of the bend they are on. These two ways of executing a corner should feel very different to you, and really help you learn to control your horses feet. Remember, they have four feet, and the more comfortable you are controlling each one independently, the easier everything will become.

Ride a figure eight, using the concepts mentioned above on the bend, and imagine that you are a pinball being released as you approach the diagonal of the figure eight. Focus on symmetry and straightness across the diagonal and impulsion will come. The more your horse steps under equally with both hind legs, and the more supple their back is, the better this will feel. Remember to organize using half halts to collect before the next bend.

Ride a 20 meter circle and slowly spiral in by asking your horses outside shoulder to step to the inside. Again, this requires you to pay attention to the function of the outside rein. Before your circle begins to feel to small, slowly spiral back out, asking your horses inside hind to step under their body, without letting their energy blow out through their outside shoulder.

Now I know that I just dropped a lot of stuffy “technical” terminology, and perhaps those of you not familiar with it have already stopped reading. But I encourage you to use this article as a template from which to develop questions. Regardless of what type of riding you prefer, these exercises WILL help both you and your horse. If it’s completely and utterly confusing, contact an instructor you like and trust and ask them to explain more. I find this all very difficult to explain and understand in writing, but once you see it visually through diagrams or by watching another rider, and especially once you FEEL it while riding yourself, it is much easier to understand. Play with these concepts first on the ground as well – then mount up and try them while riding. And feel free to ask me via e-mail or phone for clarification as well. Finally, know that addressing issues of straightness will result in a healthier and stronger body for both you and your horse. This will lead to way more enjoyment in the long run…